On the Fringe: Urban Colonial Planning in Rooster Town, Manitoba

Canada has a long history, far longer than our colonial history. Indigenous people have occupied Canada since time immemorial, and continue to occupy their traditional lands. Specifically, in Winnipeg, Manitoba Indigenous people have nomadically occupied the area around the Forks of the Assiniboine and Red River for thousands of years. Since the forceful presence of colonialism in Canada, Indigenous people have been systematically expropriated from their lands and forced to the fringes outside of the urban environment. This is precisely the case in Rooster Town, Winnipeg. David Burley in his research on Rooster Town narrates this process eloquently with the following:

The expropriation of autochthonous groups from their soil has been not just an exertion of physical force, it also has been a cultural process whereby colonizers have distinguished their self from the colonized and racialized other and have claimed their own greater beneficial, scientific, and moral use of space otherwise wasted, despoiled, and defiled by prior inhabitants.[1]

Urban discrimination in the form of racism, colonial municipal planning and societal alienation led to the expropriation of many Métis families from Rooster Town in Winnipeg in the wake of city planning and building. Informal building practices, settlement patterns and building tectonics are vital threads of urban fabrics. These informal settlements tell a truth more honest than that of colonial urbanism in Canadian cities such as Winnipeg. Fringe communities arise organically out of the need to shelter families and are constructed by the end users of the buildings, unlike many of the neighborhoods in Winnipeg where professionals design and construct homes for prospective residents. In contrast, informal architecture responds more critically to the needs of the residents. Vernacular architecture is the form of architecture that arises when mistakes have severe consequences. Fringe settlements such as Rooster Town are lost pieces of Canadian history that demand privileging in architectural history.

The expropriation of Métis families in 1959 in Rooster Town, Winnipeg illustrates clearly Canada’s broader agenda to use urban colonial planning as a vehicle to disenfranchise and dislocate urban Indigenous people to nurture a society exclusive of urban Indigenous people.

Rooster Town was located about 3 kilometres south of the intersection of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. (Map: Jason Surkan)

The location of Rooster Town evolved with time and shifted south as Winnipeg developed. The ovals represent this shift in an abstract way as the boundaries of rooster town were often hard to determine with a fine line. There were other Métis families that lived outside, but near these lines and were part of Rooster Town. Map redrawn (Jason Surkan) from: David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 9.

The intersection of the Red and Assiniboine River has provided a home for Indigenous people for thousands of years. Waterways were used as highways by canoe before the advent of roads and automobiles. Subsequently, this area was an area of great spiritual and economic activity for at least 6000 years.[2] There is extensive evidence of petroglyphs, rock art and artifacts in the area. The canoe route that intersects here connected many of the plains first inhabitants such as but not limited to the Ojibway, Assiniboine, Anishinabe, Sioux, Salteaux, Cree, and Lakota. The traditional way of life for Indigenous people here existed for thousands of years until 1738 with the arrival of the first colonists in this area.[3] This lifestyle remained relatively unchanged for around a century until the decline of the fur industry, and the end of the Bison hunt in 1885. This pushed the Métis to a series revolts from 1869-1885, and ended tragically with the loss of a prominent leader, Louis Riel.[5] These compounding events forced many Métis families into a sedentary lifestyle where a shift from economic and social prowess turned to struggle. The historically nomadic Métis families joined their more sedentary kin in an area near The Forks known at the time as the “Red River Settlement”. Métis families had settled as early as 1816 on river lots along the Red River.

This map shows a plan of the Red River Settlement as it was in June 1816. Note the division of river lots along the Red River. This map clearly illustrates that Métis had settled in area along river lots by 1816. The city of Winnipeg grew outwards from the original centre near what was Fort Douglas. Map From: University of Manitoba Libraries. Accessed through: Wyman Laliberte, “Manitoba Historical Maps,” Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/manitobamaps.

This map shows the pre-settlement trails that existed around Winnipeg. These trails along with the confluence of the Assiniboine and Red River are part of the reason for the location of present day Winnipeg. Drawn by Martin Kavanagh. Accessed through: Wyman Laliberte, “Manitoba Historical Maps,” Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/manitobamaps.

Disenfranchisement of Indigenous people from their ancestral lands began prior to settler contact on the lands of what was to become Winnipeg. In 1670, all lands that’s watershed flowed into the Hudson Bay were possessed by the Hudson’s Bay Company through a charter. Possession over these lands by the Hudson’s Bay Company remained until the province of Manitoba was formed in 1870, becoming the fifth province in Canada and shortly after Winnipeg was incorporated in 1873.[6] The incorporation of the city of Winnipeg gave rise to the first forms of municipal colonialism that sought control of urban Indigenous people.[7] The municipality now had institutional power to violently oppose the Métis who resided on the land that became Winnipeg.

This map clearly illustrates that the area of Winnipeg is the centre of settlement in Manitoba pre-confederation. Indigenous people moved nomadically throughout the area seasonally dependent on supply of resources. Métis families began to settle down in the Winnipeg area as early as 1816. Map From: Province of Manitoba Dept. of Industry and Commerce. Accessed through: Wyman Laliberte, “Manitoba Historical Maps,” Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/manitobamaps.

These Métis families were fighting for their seat in the new world order. [8] Municipal powers regulated and controlled urban Indigenous people in Winnipeg using multiple tactics that included civic power, police officers and health authorities. Through these agents, the municipality created a false perception that popularized and legitimatized to the greater public the idea that Indigenous people are ill-suited to urban environments. This vision of Indigenous people quickly circulated throughout the public and municipal colonialism gained total power in Winnipeg. [9] State endorsed racism often created fatal violence and sexual assault of Métis women and men living in Winnipeg. Most notably, a series of attacks occurred during the fall of 1870 with during what is known as the Reign of Terror.[10] Tensions between Métis people and English Protestants flared when Riel ordered the execution of Thomas Scott.[11] As a result, the Canadian government deployed the Red River Expedition Force (RREF) to “control” the Métis in Red River. By 1877, the railway reached Winnipeg, which made possible a massive influx of immigration and furthered racial based tensions between immigrant and Indigenous people.[12] Increased immigration pushed Indigenous peoples to the fringes of cities, away from their original lands. These compounding events increased the City of Winnipeg’s municipal colonial planning authority over it’s original inhabitants.

This image shows a Métis family living out on the land during summer months with a Red River Cart and Tipi Poles. The above factors led to a time of economic and social struggle for Métis families. Photographer: McKenzie, Peter. (ca. 1906) Accessed Through: Danielle Kastelein, “Material Culture: Red River Cart,” The Métis Architect…(?), 2016, accessed December 09, 2016, https://metisarchitect.com/2016/07/29/the-red-river-cart/.

The rise of the Métis Nation simultaneously with the race for land ownership and power by colonists created polarizing tensions in Manitoba that ended in fatal violence in many circumstances. After the defeat of the Métis in Batoche, Saskatchewan under Riel, and his subsequent hanging the Métis nation underwent a period of transition from economic and social prominence to tough times socially, politically and economically. Métis people slowly dispersed into smaller family bands and were pushed to the fringes of civilization to exist quietly in the shadows of colonial powers in fear of racial generated violence and crippling discrimination from settler society. Métis people lived on crown lands known often as road allowances where they remained out of sight and out of mind. The City of Winnipeg was now able to fully implement colonial planning tactics to develop the cities fabric as Indigenous people were pushed to the city fringes. The colonial city plan was exclusive of Indigenous planning values. Indigenous people have an almost contrasting perception of land use as it pertains to planning that is narrated eloquently by the following quote:

Indigenous people understood the land as inclusive of Earth, water, and sky. Land (and water and sky) has spiritual significance. Their beliefs manifest in cosmological constructs and narratives, in their considered use of physical resources, and in the marking of places of social gatherings for rituals and ceremonies. Their relationship with landscape involved complex and interdependent constructs that gave them identity and gave the land meaning. The ideal of individual ownership of land—central to European culture and mission—was unknown to them.[13]

This stark contrast in values towards land ownership furthered the ease with which the City of Winnipeg morphologically grew in a colonial form. The city was set on several intersecting Cartesian grids, despite geographical and topographical complexities that naturally resisted this colonial planning tactic. Three Cartesian grids are visible in Winnipeg that intersect at obscure angles. The application of a strict municipal colonial order left little room for Indigenous people within the urban fabric. This form of development continued in parallel with the existence of Rooster Town. Rooster Town existed south of the city centre which allowed it to exist relatively uncontested until the 1950’s.

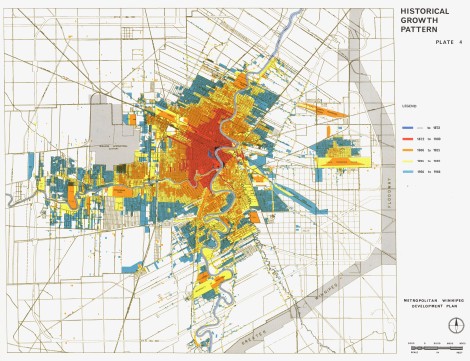

This map shows the historical growth of Winnipeg and the intersecting Cartesian grids at play. Winnipeg grew morphologically from the city centre around near what was Fort Douglas. The area of Rooster Town is not properly recorded on this map, as expected. It is evident that when this map was completed in 1966 by the City of Winnipeg Planning Department that Rooster Town was not considered a form of development prior to 1950. This is not surprising, as the City villainized residents to forcefully expropriate them from their land. Accessed through: Wyman Laliberte, “Manitoba Historical Maps,” Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/manitobamaps.

This map was drawn from three Aerial images of Rooster Town taken by Natural Resources Canada in spring of 1929. Rooster Town was at it’s peak while other communities suffered the Great Depression. The community numbered several hundred residents at this time and was dispersed throughout poplar bluffs and shortgrass prairie. It is clear that Rooster Town developed organically through necessity, and the municipality had no control over the development here. Note how the families form circular nodes in several instances. This formation is much closer to that of their Indigenous ancestry. Métis families would camp during bison hunts in a circle formation with their Red River Carts in a circle, and families protected in the centre. Municipal planning is seen on the edges of these images, and are a stark contrast to Indigenous morphology as seen in Rooster Town.

There was an overall trend to suburbanize Canadian cities after World War Two in response to desired living conditions. Families sought to own detached homes and to have individual lots.[14] This created a major increase in demand for fringe lands adjacent to the city centre as urban sprawl occurred, which included the lands of Rooster Town. This land was becoming incredibly valuable to developers because of negotiations between the City of Winnipeg and CNR to remove their seldom used East-West line on what is now Grant Avenue. Grant Avenue was to become a main transportation corridor in south Winnipeg. [15] For development to occur on these lands, the residents of Rooster Town would have to vacate the lands. In response to developer demands, the City of Winnipeg subsequently villainized Rooster Town’s residents to the Winnipeg public to legitimatize their swift and inhumane removal from their traditional lands. This was achieved in several ways by City officials. Media outlets such as the Winnipeg Free press and Winnipeg Tribune played an integral role in communicating city initiated municipal colonialism to the broader public. They reported regularly on acts of vice, violence and poverty that occurred in Rooster Town with headlines such as: “Village of Patched-Up Shacks Scene of Appalling Squalor”.[16] David Burley describes the how the city employed municipal powers against Rooster Town’s residents here:

Besides a racism that was systemic in the institutions and practices of the local state, colonialism was expressed in the anxieties of middle-class suburbanites who feared that their dreams of a healthy and safe place to raise children and acquire home ownership were threatened by racially mixed families (and those who lived like them) who seemed indifferent to the central values of hard work, cleanliness, and sobriety, and whose children were assumed to be unclean and to carry contagious diseases.[17]

Misinformed suburban anxieties rapidly developed in privileged, immigrant suburbanites. Rooster Town’s residents developed quite a public notoriety as dangerous people whose existence diminished adjacent real estate values, which were to become some of the most valuable properties in Winnipeg.[18] School trustee Nan Murphy described the homes in Rooster Town as, “a picture of squalor and filth.” She stated that: “The parents have no moral responsibility—they are shiftless and even when clothes and things are given to them, they sell them”[19]. This quote illustrates a disparity in the Métis families living within Rooster Town, where opportunities like this had to be capitalized upon to aid in survival. The Métis are a resilient and opportunistic people out of necessity. Furthermore, the Tribune reporter Bill MacPherson wrote about parents warning their children, “Whatever you do …, do not touch the Rooster Town children. You might get a skin disease”.[20] These publications circulated through rumour throughout the city and had irreversible effects towards public perception of the residents of Rooster Town. Rooster town was a vibrant, generous community that took in many Métis families who were in desperate need of shelter and resources. Families worked together as tight knit units to survive the hardest of times. Ironically, the family values within Rooster Town families did not differ much from immigrant families who demonized the residents of Rooster Town and their actions that were necessary to ensure survival. David Burley writes the following regarding life in Rooster Town:

The rundown shacks of Rooster Town may not have seemed like homes to city authorities and welfare officers, but for the poor, often working poor, who lived there represented success in surviving in a harsh climate and an even harsher social system. Their eviction, with token compensation, rendered the residents of Rooster Town homeless. [21]

The homes of Rooster Town were constructed almost entirely of found materials in the surrounding areas. The Canadian National Railways unknowingly provided most of the building materials for the homes. The railways Harte subdivision stored boxcars in off season, and their wooden partitions provided ideal home building material.[22] It is evident in this image that the siding is from CN boxcars. Also, this image shows the close kinship ties within Rooster Town. In many cases, several generations lived together in one home. This is similar to how their ancestors lived before colonization. Image From: PC18/5874/18-5874-003, Winnipeg Tribune Collection, Department of Archives and Special Collections, Elizabeth Dafoe Library, University of Manitoba.

Furthermore, Indigenous people were represented to not be fit as urban dwellers as settlers. They were seen to be rural beings, incapable and incompetent within urban fabric by colonialists. Jane M. Jacobs has argued the following:

“The relations of power and difference that are imperialism have been and continue to be articulated and enforced in and through the organization of space and the meanings assigned to space. Within cities that have engaged in imperialist enterprises, the space needed for living and working has been allocated—won or lost—through the contention of differing claims from settlers and the colonized to home.”[23]

Indigenous people have lost claim in Canada to their traditional lands in urban environments, and hold land bases primarily outside of urban centres because of municipal colonialism. Colonialists sought to place “order” upon the land and through commodification created the idea of property ownership. This constructed reality left little room for Indigenous participation in urban planning in Canadian cities, such as Winnipeg. Municipalities created by-laws, regulations, and services that set up a defined way to correctly use urban space. Undesirable people were sanctioned as “vagrants,” “nuisances,” and “prostitutes”—most often applied to urban Indigenous people, who did not maintain a place in colonial municipalities economic, social, and political system. [24]

There is deep seated irony within the ideology of Indigenous people not being fit urban beings, as in almost all cases of urbanization in a Canadian context, Indigenous people were always present in large numbers where these major cities are settled today. Many Canadian city names are derived from Indigenous Language. Winnipeg is in it’s current geographic location because of the strong presence of Indigenous people at the time of the arrival of settlers at The Forks. The combination of negative press and the villainization of Indigenous people in an urban environment through using municipal colonialism tactics now justified the City of Winnipeg for publicly supported erasure of Rooster Town.

This drawing shows an architects rendering of the proposed Grant Park Plaza that took the place of Rooster Town. Surface parking and a shopping complex was privileged above the homes of hundreds of Indigenous residents of Rooster Town. The homes in this image illustrate an ideology of suburban housing with large, gridded lots and parking for automobiles. This rendering shows strict order in planning tactics, which was a stark contrast of informal settlement of Rooster Town. Image From: Winnipeg Free Press, 2016. [25]

On August 18th, 1959, a devastating blow was dealt to the remaining fourteen families who were holding out in Rooster Town. The City of Winnipeg approved development application for a 118-acre $10,000,000 shopping centre on the lands of Rooster Town. The anchor tenant of the mall was the Canadian Branch of a large American Banking Institution.[26] The complex also included numerous office buildings, a large shopping centre and surface parking for middle-class suburban families to enjoy. It is quite evident that the City placed economic needs of the privileged middle class over the needs of a century old marginalized community. Secondly, a rapid increase in population in the surrounding area of Rooster Town put ever increasing pressure on local schools. Subsequently, Grant Park High school was also constructed on this site, erasing the very last refuge for Rooster Town’s residents. Residents were offered a small token of $75 if moved from Rooster Town by May 1st, and $50 if they moved by June 30th. They faced eviction proceedings and the burning of their homes if they resisted.[27] The development of Grant Park Plaza and high school illustrate clearly Winnipeg’s agenda to assert municipal colonialism over the original inhabitants of Rooster Town.

This clipping is a scan of the notice of eviction the residents of Rooster Town received on May 13th, 1959. Accessed From:

The remaining families that were forcefully moved off their lands in Rooster Town were some of the most economically and socially marginalized residents of Rooster Town. Many of the families sought to remain kinship ties and relocated to Henry Avenue, an incredibly deprived area of Winnipeg that borders the rail lines. Some families were not so lucky to find suitable housing and became homeless after the eviction. [28]

Conclusion:

The erasure of an Indigenous community within Winnipeg illustrates broadly Canada’s agenda to employ the use of colonial planning tactics to disenfranchise Indigenous peoples from their original lands as they evolved into urban environments. Disenfranchising Indigenous people from their traditional lands is deeply rooted in Canadian history, and in the case of Rooster Town, apexed with pressures to suburbanize Winnipeg in a post World War Two era supported by suburban anxieties of immigrant culture. Rooster town was not a unique case in Canada. In Manitoba alone, there was at least 26 more Indigenous fringe communities that were erased to make way for suburban development.[29] Within all of Canada, it is possible that there were hundreds of undocumented fringe communities. Similar disenfranchisement of urban Indigenous people through villainization and municipal colonialism took place from coast to coast in Canada in cities such as Vancouver, Toronto, Hamilton, Kingston, and Halifax.[30] Research into these communities is surfacing more stories of fringe communities and the atrocities that occurred with regards to the erasure of them. They are important lost pieces of Canadian architectural history. Hopefully, this area of research will serve to bring awareness to these communities so that Canada can move towards an era of reconciliation.

The recent surge of research into these communities speaks great volumes of the resilience of the Métis people. Louis Riel, a prominent Métis leader was quoted in July of 1885 with the following statement, “My people will sleep for one hundred years, but when they awake, it will be the artists who give them their spirit back.”[31] Despite centuries of oppression, systematic assimilation and cultural genocide Indigenous people are now at the headlines in Canada. On May 27th, 2016, an unprecedented and historical memorandum of understanding between Canada and the Manitoba Métis Federation was signed following a Supreme Court land ruling. This ruling is an acknowledgement for the Manitoba Act of 1870 that was never honoured. The province promised 5,565 square kilometers of land to be set aside for the children of the Red River Métis.[32] This historical ruling is one of many compounding positive events for the Métis nation. Indigenous people have permeated all levels of governance, planning departments and the architectural profession in Winnipeg. Winnipeg elected its First Indigenous Mayor in 2014, Brian Bowman. Having Indigenous leaders inside of municipal institutions is the only way to begin to break down barriers that were set up to impede Indigenous progress within urban environments. These leaders still face no shortage of negative press that create racial anxieties within Winnipeg. In 2014, MacLean’s released an article outwardly stating that Winnipeg is Canada’s most racist city. Press such as this perpetuates negativity, and is a continuum of Canada’s colonial legacy. Indigenous people are the fasting growing demographic within Canada and are rapidly urbanizing.[33] It is hopeful that City planning departments will work synergistically with Indigenous people to create welcoming, urban environments within Canada to foster positivity and success of all Indigenous people, that will create more inclusive cities for all Canadians.

Timeline of Rooster Town. Click for larger image. (Drawing: Jason Surkan)

Left: This map show the informal settlement versus colonial settlement patterns in Rooster Town in 1929. Image traced from Natural Resources Canada Photographs. Note the stark contrast in planning tactics, this eventually led to devastating friction between the City of Winnipeg and Rooster Town’s Residents. (Drawing: Jason Surkan)

Rooster Town, March 1959 Gerry Cairns / Winnipeg Free Press Collection, Archives of Manitoba 4 March 1959

Winnipeg Free Press reporter outside 1145 Weatherdon Avenue in Rooster Town, March 1959 James and Mary Parisien lived at 1145 Weatherdon Avenue in 1959. They had lived there for only a year or two but had resided in south Fort Rouge since the 1920s. Before them, the house had been occupied by Ernest and Julia Lepine, who earlier had lived on Ash Street. The house number provided the reference point from which the addresses of the unnumbered houses could be reckoned. Despite their simple construction, the shanties displayed some variations in status. The wooden shingle siding of the Parisien residence distinguishes it from the tar-paper cladding of some of its neighbours. Beside 1145 Weatherdon is a home with painted trim and sashes. Gerry Cairns / Winnipeg Free Press Collection, Archives of Manitoba 4 March 1959

Gerry Cairns / Winnipeg Free Press Collection, Archives of Manitoba Ernest and Elizabeth Stock were evicted from Rooster Town in 1959. March 4, 1959

Bibliography:

Anderson, Alan B. Home in the City: Urban Aboriginal Housing and Living Conditions. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013. Print.

Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion and Darren R. Prefontaine. Metis Legacy, Volume I. Winnipeg: Pemmican Publications, Gabriel Dumont Institute and Louis Riel Institute, 2001: pp. 1-2.

Brandon, Josh, and Evelyn Peters. Moving to the City: Housing and Aboriginal Migration to Winnipeg. Winnipeg: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Manitoba, 2014.

Burley, David G., “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013): , doi:10.7202/1022056ar.

Jacobs, Jane M. Edge of Empire: Postcolonialism and the City. London: Routledge, 1996.

Natcher, David C., Ryan Christopher Walker, and Theodore S. Jojola. Reclaiming Indigenous Planning. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2013.

Peters, Evelyn J., and Chris Andersen. Indigenous in the City: Contemporary Identities and Cultural Innovation. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013.

Peters, Evelyn J., and David Newhouse. Not Strangers in These Parts: Urban Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa: Policy Research Initiative, 2003.

Peters, Evelyn J. Urban Aboriginal Policy Making in Canadian Municipalities. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

St-Onge, Nicole, Carolyn Podruchny, and Brenda Macdougall. Contours of a People: Metis Family, Mobility, and History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

Turner, By: Randy, Posted: 01/29/2016 12:00 PM | Comments:, and Last Modified: 01/31/2016 1:38 PM | Updates. “The Outsiders.” Winnipeg Free Press. Accessed December 09, 2016. http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/The-outsiders-366764871.html.

Newspaper Sources:

“Fort Rouge Centre.” Manitoba Free Press (Winnipeg), April 20, 1911. Accessed December 8, 2016.

“Grant Ave. Seen as Thoroughfare.” Winnipeg Free Press, June 17, 1953. Accessed November 20, 2016.

“Huge Shopping Area to Cost $10 Million.” Winnipeg Free Press, 18 August 1953. Accessed December 8, 2016.

News, CBC. “Canada and Manitoba Métis Federation Sign MOU following Historic Supreme Court Land Ruling.” CBCnews. 2016. Accessed December 09, 2016. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/metis-federation-of-manitoba-signs-mou-1.3604370.

“Rooster Town.” Winnipeg Free Press Newspaper Archive Search Old Newspapers – NewspaperArchive.com. Accessed December 09, 2016. http://archives.winnipegfreepress.com/tags/rooster-town.

Aerial Photography: (Natural Resources Canada, Google Earth)

“National Air Photo Library.” Natural Resources Canada. Images: A1221_007, A1221_008, A1221_009. 1929. Accessed December 09, 2016. http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/earth-sciences/geomatics/satellite-imagery-air-photos/9265.

“National Air Photo Library.” Natural Resources Canada. Images: A12980_007, A12980_008, A12980_009. 1950. Accessed December 09, 2016. http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/earth-sciences/geomatics/satellite-imagery-air-photos/9265.

Maps:

Laliberte, Wyman. “Manitoba Historical Maps.” Flickr. Accessed December 09, 2016. https://www.flickr.com/photos/manitobamaps.

Miscellaneous:

“Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies and Applied Research Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture.” The Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture. Accessed December 09, 2016. http://www.metismuseum.ca/resource.php/07260.

“Louis Riel Quotes.” Louis Riel Quotes | Manitoba Metis Federation Inc. Accessed December 09, 2016. http://www.mmf.mb.ca/louis_riel_quotes.php.

“Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960.” Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960 | Érudit | Urban History Review V42 N1 2013, P. 3-25 |. Accessed December 01, 2016. https://www.erudit.org/revue/uhr/2013/v42/n1/1022056ar.html.

Winnipeg, City Of. “History of Winnipeg.” Historical Dates 1670-2012 – History – City of Winnipeg. Accessed December 09, 2016. http://winnipeg.ca/History/HistoricalDates.stm.

Endnotes:

[1] David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 3.

[2] City Of Winnipeg, “History of Winnipeg,” Historical Dates 1670-2012 – History – City of Winnipeg, accessed December 09, 2016, http://winnipeg.ca/History/HistoricalDates.stm.

[3] City Of Winnipeg, “History of Winnipeg,” Historical Dates 1670-2012 – History – City of Winnipeg, accessed December 09, 2016, http://winnipeg.ca/History/HistoricalDates.stm.

[4] Lawrence Barkwell, “Contributions Made by Métis People,” Louis Riel Institute.

[5] Nicole St-Onge, Carolyn Podruchny, and Brenda Macdougall, Contours of a People: Metis Family, Mobility, and History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012).

[6] http://winnipeg.ca/History/HistoricalDates.stm

[7] David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 3. Dr. Jordan Stranger-Ross, a professor at the university of Victoria first coined the term “Municipal Colonialism”.

[8] Alan F. J. Artibise stated that businessmen sought municipal incorporation of Winnipeg just a year after the birth of Manitoba to finance the infrastructure needed to advance their individual and collective commercial ambitions. True; however, incorporation also separated the city from the province and gave settler-colonists their own level of government and fiscal resources, beyond the reach of a legislature controlled in its first Parliament by Métis members. Winnipeggers objected to having their tax dollars’ fund schools and other services for poorer Métis communities. Artibise, Winnipeg, 12–15; David G. Burley, “The Emergence of the Premiership, 1870–1874,” in Manitoba Premiers of the 19th and 20th Centuries, ed. Barry Ferguson and Robert Wardhaugh (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 2010), 16–17.

[9] David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 10.

[10] “Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies and Applied Research Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture,” The Virtual Museum of Metis History and Culture, , accessed December 09, 2016, http://www.metismuseum.ca/resource.php/07260, 3.

[11] A. H. de Tremaudan, “The Execution of Thomas Scott,” Canadian Historical Review, Vol. 6, Sept. 1925: 229.

[12] City Of Winnipeg, “History of Winnipeg,” Historical Dates 1670-2012 – History – City of Winnipeg, accessed December 09, 2016, http://winnipeg.ca/History/HistoricalDates.stm.

[13] Davidson-Hunt and F. Berkes, Survey of First Nations spatial and environmental perception. “Learning as you journey: Anishinaabe perception of social-ecological environments and adaptive learning,” Conservation Ecology, 8 1 (2003): 6. Available online at: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol8/iss1/art5/. Natural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba (accessed November 27, 2016).

[14] The above map illustrates Winnipegs Agenda to colonize the land and people of Winnipeg through morphological development of urban fabric. This is a common theme urban planning in Canadian Cities and for decades remained uncontested in theory.

[15] “Grant Ave. Seen as Thoroughfare,” Winnipeg Free Press, June 17, 1953, accessed November 20, 2016..

[16] Winnipeg Free Press. December 20, 1951.

[17] David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 18.

[18] Winnipeg Free Press. April 11, 1959. John Dafoe wrote: And as they moved, their place was taken by some of Winnipeg’s most elegant houses. The worthless prairie on which the Rooster Towners squatted became the city’s most expensive residential land.

[19] David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 3.

[20] Winnipeg Tribune. 1959. Bill MacPherson.

[21] David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 18.

[22] Winnipeg Free Press. April 11, 1959.

[23] Jane M. Jacobs, Edge of Empire: Postcolonialism and the City (London: Routledge, 1996).

[24] David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 3. Burley References Penelope Edmonds, “Unpacking Settler Colonialism’s Urban Strategies: Indigenous Peoples in Victoria, British Columbia, and the Transition to a Settler-Colonial City,” Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine 38 (Spring 2010): 4–20. Karl S. Hele has made a similar point about the effects of municipal ordinances in Sault Ste. Marie: after incorporation in 1871, differential property tax rates favouring settlers and discriminatory liquor regulations made it economically impossible for many Métis families to remain and drove them away or beyond the town’s margins. “Manipulating Identity: The Sault Borderlands Métis and Colonial Intervention,” in The Long Journey of a Forgotten People: Métis Identities and Family Histories, ed. Ute Lischke and David T. McNab (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2007), 171–3

[25] Randy Turner, Posted: 01/29/2016 12:00 PM | Comments:, and Last Modified: 01/31/2016 1:38 PM | Updates, “The Outsiders,” Winnipeg Free Press, , accessed December 09, 2016, http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/The-outsiders-366764871.html.

[26] Winnipeg Free Press. August 18, 1959.

[27] “City Wants Rooster Town Land; Cash Offer to Squatters,” WT 17 April 1959; “Cornerstone for School,” WFP, 19 May 1959; “$75 Lures Shacktown Families,” WFP, 29 May 1959; Minutes of the City Council of the City of Winnipeg for the Year 1959, 220; and “Removal of Squatters from Land Sold to Winnipeg School Division No. 1,” City Council Files, file F. 1451(253), CWARC.

[28] David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 18.

[29] In 1956 the Manitoba government hired Jean H. Lagassé to study the province’s Aboriginal population. His report three years later identified twenty-six “fringe settlements,” including Rooster Town, inhabited by people of “Indian ancestry.”

[30] David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960,” Urban History Review 42, no. 1 (Fall 2013), ?.

[31] “Louis Riel Quotes,” Louis Riel Quotes | Manitoba Metis Federation Inc., , accessed December 09, 2016, http://www.mmf.mb.ca/louis_riel_quotes.php.

[32] CBC News, “Canada and Manitoba Métis Federation Sign MOU following Historic Supreme Court Land Ruling,” CBC news, 2016, accessed December 09, 2016, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/metis-federation-of-manitoba-signs-mou-1.3604370.

[33] Alan B. Anderson, Home in the City: Urban Aboriginal Housing and Living Conditions (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013).

Pingback: Reconciliation and the City – Dear Winnipeg·

My dad was raised in Roostertown and they were one of the last families to leave as they had their home and land expropriated by the city in fact like you wrote they did change or make new by laws to evict and relocate the residents of Roostertown. Thank you for sharing your article and I will be showing this to my dad.

Thanks Darrell Sais