From the time of road allowance communities, the campaign towards safeguarding the notion of home and nationhood for the Métis is a battle which has and continues to be fought in many communities throughout Canada. Experiences of poverty within all three Aboriginal groups have been perpetuated by systemic discrimination and colonialism. Enduring socioeconomic disadvantages, racism, as well as the subsequent impacts of abuse that Aboriginal communities have suffered as a result of assimilation practices (Residential Schools, Indian Act) still exist and will continue its ripple effects onto the following generations. Currently, many communities are still suffering due to the deplorable housing conditions throughout Canada. Over the years these communities have seen interventions from paternalistic institutions which perpetuate a continued misunderstanding of Indigenous lifestyle differences surrounding domestic space.

It is documented that Indigenous people have a different understanding of how they perceive private and social spaces. Similarities can be found with how space is organized within group homes like the Eva Pheonix in Toronto. Furthermore, promoting the interaction between private and social realms has been shown to have an effect on the transition between homelessness and re-intergration into society. We shouldn’t confuse this type of housing project as having the same paternalistic intervention as the different subsidised housing programs provided by the government. INAC (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada) homes provide an excellent example of a structure which does not support the Métis ‘boundedness’ lifestyle described by David Burley.[2]

Community consultations and an interest in preserving cultural significance in buildings are imperative to ameliorating the quality of life within Aboriginal communities. The more people have a connection with their buildings and households the more pride they have in taking care of them.[3] In addition issues such as overcrowding cause more wear on a building thereby increasing the frequency of repairs and severity of damages incurred over a given point of time.[4] Extensive consultations and Charettes enable a designer to incorporate the wants and needs of members within a particular community, thereby resulting in more successful projects that provide safer and healthier living conditions. Furthermore, incorporating local materials and energy efficient systems and designs would also assist in having a positive impact on the projects overall for a number of reasons.

On-reserve housing is often described as unsafe, inadequate and overcrowded (Patterson & Dyck, 2015). A lack of funding has contributed to producing buildings of substandard quality which have subsequently led to an increase in maintenance costs.[5] In addition, families with low incomes have a greater difficulty in maintaining and improving their homes.[6] Overcrowding is also tied to an endless cycle of an increasing number of homes in disrepair.[7] Housing shortages, in particular, has prompted the demand for expedient access to shelter, thereby leading to a decrease in the quality of construction and design.[8] This has resulted in many individuals having to live temporary structures, often for extended periods of time.[9] Projects that have failed in producing long-lasting, safe and stable households have shown to not only overlook the needs of Aboriginal people in terms of the building’s function but also in relation the integration of cultural and spiritual elements.

Aboriginal housing projects in the past attempted to provide communities with accommodations which would meet a family’s current needs. However, the individuals involved with these projects failed to conduct thorough site visits in order to connect with the people they were trying to assist. Therefore, solutions were put into place without the consideration of the future needs of the residents; rather decisions were made in an attempt to ‘fix’ the current paradigm. In addition, it was not presumed that Aboriginal communities operate very differently from non-Aboriginal ones in relation to the length of time one family will reside in one particular household as well as access to the resources required to make adequate repairs over time. As a result, a home that was designed for a 4 person household would not necessarily fit within the model of a typical Aboriginal home. Households often include members which extend past the immediate family line such as grandparents, cousins, uncles, and aunts.[10]

A House in the First Nations Community of Pikangikum in Northwestern Ontario

What Aboriginal communities are then left with are an increasing number of homes that are in disrepair, too small to support their living conditions and often infested with mould.[11] Although these issues are largely a result of a lack of funding, problems related to overcrowding may have been avoided. Had an interview process or site visit been performed, perhaps consultants could have discovered the existence of certain cultural differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people regarding non-nuclear housing structures. Unfortunately, there is no way of knowing whether this would have freed up any information due to the closed nature of most communities, a lack of trust in the developers as well as just having not asked the right questions during the design phase.

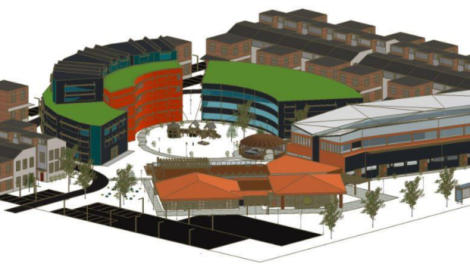

Research has documented that Indigenous people have different perceptions of private and social space. Similarities can be found with the level of organization of space within the design, principles and overall implementation of group homes such as the Eva Pheonix, and housing projects like Housing First and the ‘Urban Aboriginal village’ proposed for downtown Prince George.

‘Urban Aboriginal Village’ in Prince George

With most of these projects, it appears that a more holistic approach is being taken, allowing a neighborhood of buildings or spaces within to serve multiple different functions. In downtown Prince George a new complex run by the Aboriginal Housing Society has been described as having;

“…a combination of houses and apartments, as well as elder and child care, educational and support services, a community garden and space for spiritual and cultural practices.”

By providing a mixture of housing and services, the village would act as a self-contained neighbourhood. (M’akola Development Services)

As previously mentioned, another project entitled ‘Eva’s Pheonix’ has received a number of positive reviews and has also been recognized by the OAA, receiving the 2017 award for Design Excellence. Although this project is not specifically designed for an Indigenous community, given the growing statistic of homeless aboriginal youth, it’s not unlikely that they may be present within the facility either today or in the future. The firm designed the building to have an open, community-based format which has shown to have dramatic rehabilitative effects.

A neighbourhood within a building, Eva’s Pheonix is a 50 bed youth transitional housing, education and skills training centre. Adaptively reusing a heritage-designed warehouse, the design is organized around an expansive and spatially layered atrium awash in daylight. Ten house-like residential units activate the this main street, with sheltered entried and ground level common areas rising to the second-level private bedrooms, and support and counselling spaces on terraces above.”

OAA awards 2017 booklet, The Canadian Architect

These projects support the need for flexible, boundless community spaces within homeless housing projects. The atrium in Eva Pheonix for example assists in not only allowing for enhanced community surveillance within the space but also to allow gathering. Indigenous communities are already familiar with the integration of these elements into housing design. This is especially true for the Métis whereby the lack of boundaries set within the majority of the first ‘frontier homes’ seem to reinforce this idea. One thing is clear however that human behaviour and other social processes require specific spatial elements and in turn are realized within a space which allows them.

Eva’s light-filled unified main street stitches together both halves of the former warehouse.

Photo Credit: Ben Rahn/A-Frame

Interconnection of Houses and Main Street: (left) House stairs ascending from common areas to open second-floor corridors and private bedrooms. (right) Views of the interconnected atrium, living room and stair as seen from an open second-floor corridor.

Photo Credit: Ben Rahn/A-Frame

Consequently, it is necessary to be critical of projects which serve a particularly sensitive demographic such as Indigenous homeless people. For example, the Boyle Renaissance housing project in Edmonton was proposed as a means of affordable housing for Métis Seniors. The building includes 90 residential units that are senior-friendly/barrier-free and said to ‘cater to the needs of Indigenous people, seniors and people with disabilities’. It also showcases a stylized pattern in its facade; the cladding on two sides of the building zig-zag to form a contemporary sash motif. Although the Boyle project has been described as incredibly affordable, receiving over 4.1 million in subsidies from both the Canadian Federal and Alberta Government, there is something about the build that still feels to have fallen short. Specifically, the development leaves much to be desired within the context of respecting Indigenous design practices and a certain spiritual sensibility. Upon trying to find images of the promised features of the building such as the spiritual gathering room (said to have been designed with a ‘with a distinctive Aboriginal identity’) and the green roof; only one image was found, that of the rooftop complex. As seen below, the green roof seems to comprise of a bare concrete slab devoid of any plant material, a small fire pit can be found surrounded by an empty semi circle bench.

The Boyle Renaissance Project – Phase 2

Boyle ‘Green Roof’ Rooftop Gathering Space

To date, few projects have disclosed to have used design Charettes or another means of community consultation as a means to develop a dialogue with Indigenous community members, and fewer have provided reports documenting the process. Now with the inception of the RAIC Indigenous Task Force, Indigenous perspectives and agency will be better integrated when working with Aboriginal clients. As of 2016, 28-34% of the shelter population has been identified as Indigenous with a particular increase in urban settings. This statistic reinforces an immediate need to act in favor of providing affordable and more importantly culturally and spiritually sustainable. The responsibility should also be shared with shareholders, stakeholders, and architects to no longer support projects that reinforce certain vestiges of colonialism which so often permeate the realm of architecture. In addition, community household projects should not only address the needs of Aboriginal people in terms of the building’s function but also in relation the integration of cultural and spiritual elements. Ultimately, however, the overarching goal which should always be kept in mind is the provision of safer and healthier living conditions for Aboriginal Communities.

References

[1] Homeless and Street-Involved Métis Youth. McCreary Centre Society. 2014 http://www.mcs.bc.ca/pdf/metis_hsiys_factsheet.pdf

[2] David, Burley., “Creolization and late nineteenth century Métis vernacular log architecture on the South Saskatchewan River.” Historical Archaeology 34, no. 3 (2000): p.35.

[3] Lisa, Hardess, Rodney C. McDonald, and Darren Thomas. “Aboriginal Housing Assessment.” (2004). p.3-4

[4] Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. “Focus on Aboriginal Housing: A Chapter from the Canadian Housing Observer” (2005). p.43

[5] Lisa, Hardess, Rodney C. McDonald, and Darren Thomas. “Aboriginal Housing Assessment.” (2004). p.2-3

[6] Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. “Focus on Aboriginal Housing: A Chapter from the Canadian Housing Observer” (2005). p.42

[7]Johann, Kyser. “Sustainable Aboriginal Housing in Canada: A Case Study Report”. Housing Services Corporation, Canadian Policy Network. (2011). p. 13

[8] Ibid. 21.

[9] Kazi, Stastna.” First Nations housing in dire need of overhaul.” CBC News. Posted 2011. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/first-nations-housing-in-dire-need-of-overhaul-1.981227

[10] Lisa, Hardess, Rodney C. McDonald, and Darren Thomas. “Aboriginal Housing Assessment.” (2004). p.5.

[11] Johann, Kyser. “Sustainable Aboriginal Housing in Canada: A Case Study Report”. Housing Services Corporation, Canadian Policy Network. (2011). p. 13

Selected References

First Nation, Inuit, Métis Urban & Rural Housing Programs 2014/20, Draft Guidelines

(subject to review and approval), FIMUR 2014/20, Ontario Aboriginal Housing Services, Investments in Affordable Housing for Ontario, September 2014. http://www.ontarioaboriginalhousing.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/FIMUR2014-20GuidelinesDraftSep12-14.pdf

Caryl Patrick, Aboriginal Homelessness in Canada, A Literature Review. 2014. http://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/AboriginalLiteratureReview.pdf

Gaetz, Stephen., Dej, Erin., Richter, Tim,. Redman, Melanie. State of Homelessness in Canada. A CANADIAN OBSERVATORY ON HOMELESSNESS RESEARCH PAPER. 2016.http://homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/SOHC16_final_20Oct2016.pdf