The most recognized individual linked to any discussion of “Métis architecture”, and a pivotal influence for this project, is undoubtedly Douglas Cardinal, the prolific Canadian architect who has designed numerous iconic structures including the Museum of History in Ottawa (formerly the Museum of Civilization) and the Museum of the American Indian in Washington. Cardinal has been described in media and publications as a “Métis-Blackfoot architect” (1), “of Blackfoot and Métis heritage” (2), and a “Métis architect” (3)(4).

However, Trevor Boddy’s The Architecture of Douglas Cardinal, which remains the most widely read monograph on Cardinal’s work, avoids labeling Cardinal so specifically. Instead, there is a complexity with Cardinal’s ancestry that is summarized adequately in a 2014 Toronto Star article.

Both his mother and father were of mixed European and native Canadian blood — he was one-quarter Blackfoot and she was of German and Métis ancestry. And while Joseph and Frances Cardinal suppressed their aboriginal roots, often to the point of denial, their native genetics were written clearly on their first child’s dark face.(5)

When asked about being described as a Métis architect, Cardinal’s response is telling. “I identify as a man with Blackfoot and German roots. I am from Métis roots.”(6) Cardinal has great knowledge about Métis people and a respect for their culture through both the influence of his mother and his professional work for Métis communities such as Grouard and Bonnyville, Alberta, and Ile a la Crosse, Saskatchewan, for example. He recalls these as positive experiences, especially in Ile a la Crosse where the new school also involved restructuring the educational infrastructure to be more grounded in Métis values.

Douglas Cardinal in traditional dress (Image Source)

He also clearly understands that the Métis are a distinct people, a people that he does not necessarily identify with in terms of any precise definition of ‘Métis’. “I am not Métis in terms of that culture, per se,” he explains. “I see myself embracing both [European and First Nations worldviews]…Your identity is tied to how you are brought up by your parents, how they had to cope.” (7) Cardinal’s father, he explains, never talked about being First Nation, he just lived it. He had a deep knowledge about the ecosystem. He hunted and trapped. As a nurse, his mother taught the children to honour people and care for them.

Architecturally, this is clear in Cardinal’s writings and lectures that emphasize his worldview being framed by a rigorous First Nations philosophy, but also as someone who embraces technology, evidenced by his introduction of groundbreaking computer technology for the structural design at St. Mary’s church, for example.(8) This duo-worldview approach is perhaps most evident in Cardinal’s design for the Edmonton Science Centre where initial design sketches could be described both as classic science-fiction (elevation) and indigenous (plan).

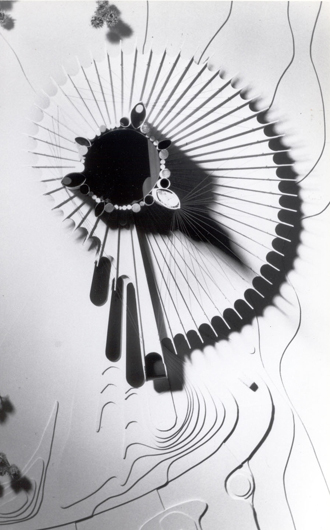

Cardinal elevations for Edmonton Science Centre (1984). Image from http://www.djcarchitect.com

Plan view of model for Edmonton Science Centre (1984). Image from http://www.djcarchitect.com

The distinction that Cardinal makes between having two worldviews and being Métis is essential to recognize in this project as it is central to the registration processes amongst the various Métis organizations across the country. The Métis Nation of Alberta, for instance, defines Métis as, “…a person who self-identifies as a Métis, is distinct from other aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation ancestry, and is accepted by the Métis Nation.” (9) Furthermore, ‘historical proof’, “refers to evidence of an ancestor who received a land grant or a scrip grant under the Manitoba Act or the Dominion Lands Act, or who was recognized as a Métis in other government, church or community records.” (9) Similarly, the Métis Nation of Ontario defines the ‘Historic Métis Nation Homeland’ as “the area of land in west central North America used and occupied as the traditional territory of the Métis or Half-breeds as they were then known.” (10) Questions of this registry are abundant, particularly from many mixed-blood people who live in Quebec or Ontario without traceable links to this prairie homeland. In any case, however, an important distinction to be mindful of is that one can not be ‘officially’ registered as both a treaty First Nation and Métis in Canada.

Yet even if not directly identifying with the Métis ‘nation’ or with a specifically registered Métis community, Cardinal’s life experience is unmistakingly linked to that of Métis people across the country, as revealed in an interview with Joseph Hall in 2014.

Those handsome, movie-Indian features gave Cardinal a rough childhood ride in 1930s and ’40s Alberta, which had built what he calls “apartheid divides” between its aboriginal and European populations. “In many cases, if you’re mixed you don’t even belong in either society,” he says. “You’re ridiculed and humiliated every day.” (11)

Cardinal’s comments echo descriptions by authors like Julia Harrison who writes that, quoting Métis leader Stan Daniels,

…the Métis have found themselves ‘caught in the vacuum of two cultures with neither fully accepting [them].’ The marginality of the Metis – who have not been given either the resources and rights of Indians or full access to white society and its advantages – has created an almost negative identity: ‘they are Metis because they are not somebody else’. (12)

Douglas Cardinal’s home studio, built from 1979-1984 in Stony Plain, Alberta. (Image from http://www.djcarchitect.com)

While evidently providing deep inner struggles and angst through repeated racism and ignorance throughout his life, like the Métis, Cardinal’s liminal identity has also provided him with a uniquely critical approach to design. His blending of First Nations values and sensibilities, along with his reverence for Western technology and its capacity for positive impact in the world, provides a distinct approach to design thinking that is universal in many aspects (Cardinal was greatly influenced by architects such as Gaudi, Borromini, and Mendelsohn, for example), and yet profoundly grounded – inspired by nature and a deep respect for the landscape, both environmentally and spiritually.

Thus, even though Cardinal may not identify as Métis, his life experiences and approach to design suggest there is very little separating him from the shared experience of many Métis people. It is a relevant discussion that will continue to surface in this project and beyond as even though one is not “Métis” by the rules governed by the relevant political bodies, a duo-worldview formed from First Nations and European perspectives provided the very foundation for Métis culture and still resonates with Métis people. Cardinal’s architecture, without question, closely reflects this kind of hybrid approach.

However, Cardinal is very clear about his overall perspective. “Annishnabe is the way I look at the world.”(13) He has been guided throughout his life by elders, such as the late William Commanda, who he calls ‘absolutely magical beings’ and who instilled in him indigenous values of striving towards a human symbiosis with nature. This was achieved for generations, Cardinal explains, through hunting and gathering societies, where nature is not perceived as something to be managed, controlled, and then patriarchally defended, as it is in agrarian societies. For Cardinal, it is for such reasons that he feels it is essential that First Nations people master technology because Western cultures are currently “playing with matches” through a worldview that is “devastating the planet.” “If we don’t respond like the Annishnabe,” he adds, “we’re done.”(15)

A question of Métis design thinking thus provokes consideration of an approach to design that foregrounds indigenous values, which are maintained through a critical awareness of both the opportunities and devastating impacts of the technological choices and methods we use. It also suggests that, if taken so broadly as to include Cardinal’s work as having ‘Métis’ characteristics (whatever those are), that designers must be deeply invested in the environmental and spiritual aspects of places and people, and that indigenous insights are invaluable in this process of making.

(Final Note: There will be a chapter in the book based off of this research that will expand on many of the topics discussed here, including further details and discussions with Cardinal.)

Notes

(1) Rabb, J. D. “The master of life and the person of evolution: Indigenous influence on Canadian philosophy.” Hidden in plain sight: Contributions of Aboriginal peoples to Canadian identity and culture. Vol. 2. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 198-224. p.217.

(2) Cook, Maria. “Douglas Cardinal: Navigating life’s curves.” Ottawa Citizen. Available online here.

(3) Barkwell, L. 2010. “Cardinal, Douglas.” Virtual Museum of Métis history and culture. Gabriel Dumont Institute. Available online here.

(4) Douaud, P. 2007. The Western Métis: Profile of a people. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre. p. 15.

(5) Hall, J. 2014. “Douglas Cardinal: an architect’s legacy.” The Toronto Star. Available online here.

(6) Personal interview. October 14th, 2014.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Boddy, T. 1989. The Architecture of Douglas Cardinal. Edmonton: NeWest. p.39

(9) http://www.albertametis.com/MNAHome/MNA-Membership-Definition.aspx

(10) Ibid.

(11) http://www.metisnation.org/registry/citizenship

(12) Hall, J. 2014

(13) Harrison, J. 1985. Metis: People between two worlds. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. p. 15.

(14) Personal interview. October 14th, 2014.

(15) Ibid.

Pingback: CONVERSATIONS: Harriet Burdett-Moulton | The Métis Architect...(?)·

Pingback: Conversations: Étienne Gaboury | The Métis Architect...(?)·